Stradivarius is a Scam

I’ve never been a violinist; I don’t remember doing more than picking up (with their permission) a friend’s violin and trying it with the bow. I probably made a sound like a Tuvan throat-singer, and alas, not in a good way. But I have played piano for going on 30 years, and I’ve been a singer for most of that time. I do have a pretty good ear. Not world-class, but pretty good. And it does extend to listening to violin music. So I feel pretty good about saying that the price-differential between an old Stradivarius / Guarnerius violin from 18th century Cremona and a new violin of a comparable level of workmanship… is a scam.

Why are we talking about this right now? Because I’ve had to edit pieces all week about people dying of preventable diseases or getting bullied because of their sexual orientation, and I just want to complain about something, and if you wouldn’t mind sitting with me for a moment while I do, then I thank you for the kindness.

A (Very) Brief History of Violin-Making from Amati to Stradivari

You may not know this stuff off-hand so I’ll quickly review it. Not least because it’s fascinating. Andrea Amati is said to have standardized the shapes of the modern violin, viola, and cello in the mid 1500s. The violins he made are still around, but are no longer widely in use. Over a century later, Antonio Stradivari and his slightly younger contemporary Giuseppe Guarneri (among others) began manufacturing what are considered the definitive violins. Those instruments—such as survive—are played, and, of course, fiercely coveted, to this day.

The highest price that someone actually paid for one of these instruments was more than ten million US dollars. It was a violin. Why so cheap? Because there are hundreds of Stradivarius violins. A Stradivarius Viola, of which there are only ten extant, was put on the market in 2014 for a cool 45 million. It didn’t sell.

Stradivarius was not the Last Word in Violin-Making

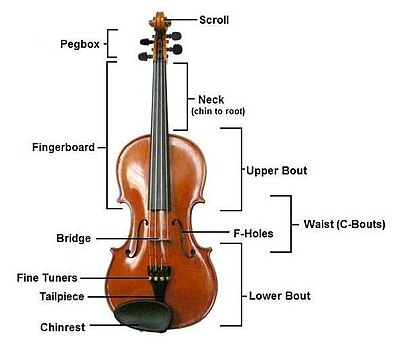

One thing that usually gets left out of these conversations, but that I find interesting. Even if the body of the violin was made in the 17th or 18th century, the rest of the instrument, as a rule, was not. I’d love to nerd out for like 20 or 30 column inches about the specifics. But suffice it to say that the fingerboard of the violin used to be almost parallel with the body. But in the 19th century, the fingerboard was tilted away from the instrument, raising the strings off the instrument, increasing their tension, and allowing string players to make a bigger sound. They also made the fingerboard longer, allowing them to play higher pitches.

The design of the body of the instrument has not changed. But the design of most every other part of the instrument has changed a great deal, indeed. The pegbox and the scroll are the same. But luthiers have added spikes to the ends of cellos. Violins and violas now sport comfy chin-rests. And so on.

I review these changes because I find the history compelling in their own right. But also because, if we so unreservedly revere Stradivari and Guarneri and their ilk to the point where people are paying millions for a single instrument, would you not think that their designs would have remained unsurpassed?

Why So Expensive?

The virtuoso violist David Aaron Carpenter (and my former high school classmate… God, he was awesome to listen to close up) said of the difference between a Stradivarius instrument and a modern instrument: “If I had to compare it to another field of creation, I’d say it’s like asking an art lover to choose between the ‘Mona Lisa’ and a perfect reproduction of the ‘Mona Lisa.’” But Leonardo’s masterpiece wasn’t updated by some 19th century engineers to make it bigger and brighter. It seems to me that when it comes to altering a Stradivarius so that it will project better in the huge modern auditoriums, at least a dozen considerations are negotiable. But when it comes to selling the Stradivarius, somehow it is still a pristine work of art; a window into a lost world.

All of this would just be kvetching if these violins sounded demonstrably better than their modern peers. But a bunch of scientists eventually did a blind-test. Violinists wearing dark goggles (so they could not see whether they were playing a Stradivarius or a modern instrument) played the same short phrase on two dozen or so different instruments. Half of the violins had been made by Stradivarius. The researchers found that audiences could not tell the difference between the the old instruments and the new. Or, at worst, actually preferred the new instruments. The study was conducted in 2014, which, ironically, is the year the viola went on the market for $45 million.

I Can Admit: It would be Nice if the Hype were Real

I am, as it happens, a romantic at heart. Albeit a disappointed one. And so of course the lore of the great Cremonese luthiers fascinates me. Did you know, for instance, that the wood for a violin has to come from a place with cold winters? It’s the coldness of the winters that causes those alternating red-and-yellow grains in the wood. Red and tight for winter, yellow and expansive for summer? The grain traditionally runs in straight lines from the top of the instrument to the bottom. And it’s said that the grain helps control how the violin vibrates when the player draws horse-hair to steel-wrapped-nylon. But that bit about the grain may be bullshit as well. Because there is more than one way to cut wood to make your violin.

So no, I’m not completely insensitive. But why am I bringing up any of these complaints? What does the myth of the Stradivarius mean in practical terms? Well first, that an old Cremonese instrument might cost ten times what even the best modern instruments would cost. Which effectively means that an elite instrumentalist tends not to own their own instrument. Which in turn means the musician is beholden to wealthy benefactors and faceless organizations for the use of their instruments.

What does the Overblown Hype do to the Prestige of the Instrument?

Which in turn raises several questions. What happens to the prestige of the owner when it is demonstrated in a double-blind experiment that their instruments produce an equivalent or slightly inferior sound as compared to the work of modern master-luthiers? So far, the answer is: nothing. But what happens if, as is more common with more pop-oriented musicians, the beneficiary of a corporation’s Stradivarian largesse were to wax political? Are there behavior clauses written into the contracts that stipulate the loan is only good, provided the instrumentalist behave?

Borrowing a Stradivarius is a Huge Honor. But at What Cost?

I haven’t heard of a wealthy benefactor withdrawing their loan. Is that because the borrower is free to do as they will, political or otherwise, or is it because they wouldn’t dare jeopardize their relationships? Think this is so far-fetched? Remember when John Cena had to apologize for calling Taiwan a country? The nerve. Referring to a self-governing land-mass as a country. Doesn’t he know that a country is whatever allows him to sell The Fast and the Furious 12: Now with Spaceships and Shit to as many Chinese theatergoers as possible? Cena is not the first, nor will he be the last, performer to compromise for a business relationship. Maybe Tchaikovsky’s violin concerto doesn’t sound different whether the violinist is political or not. But it obviously made a difference to Tchaikovsky. Who is thought to have committed suicide after writing his Sixth Symphony. Because his family could not accept his homosexuality.

Goddamnit this was just supposed to be a light piece.

But the point stands. How can you be apolitical and play Tchaikovsky? Maybe your interpretation doesn’t sound political as such; but how can you, for example, travel to Hungary or Poland or Russia or the United States or any of these other vitriolic anti-queer countries and play Tchaikovsky, oblivious of the larger context? I think a performer may be vaguely aware of such things but may blink at just the right moment in order to keep on performing and making money. And part of that keeping-on is getting to continue to use their prestigious (but not all that exceptional) instrument.

The Myth of the Stradivarius

As long as a Stradivari or Guarneri is more than just an instrument; more than the sum of its parts; as long as the myth of the instrument matters more than does the instrument itself, it will also cost more than almost any instrumentalist can afford. And thus will represent a lien on that instrumentalist’s talent by a corporation usually associated with trade, not with music. And that’s not even mentioning how the price of these instruments is driving up the counterfeit market.

Okay. One last thought. Hear me out. If these instruments are so perfect, how is there even a counterfeit market in the first place? Shouldn’t these people who claim to come in their pants the moment they hear the perfection of tone that only a Stradivari is capable of producing be able to tell the true instruments from the fakes? Look at this article on how to sniff out a fake Stradivarius. And note how infrequently the writer mentions the purity of the tone as a deciding factor in any determination.